- #Cashflows at begining of project how to

- #Cashflows at begining of project plus

- #Cashflows at begining of project free

#Cashflows at begining of project plus

Indeed, the unearmarked part of the C/F-the return-of-capital items plus profits after taxes-is usually the principal source of funds for amortizing debt.

#Cashflows at begining of project free

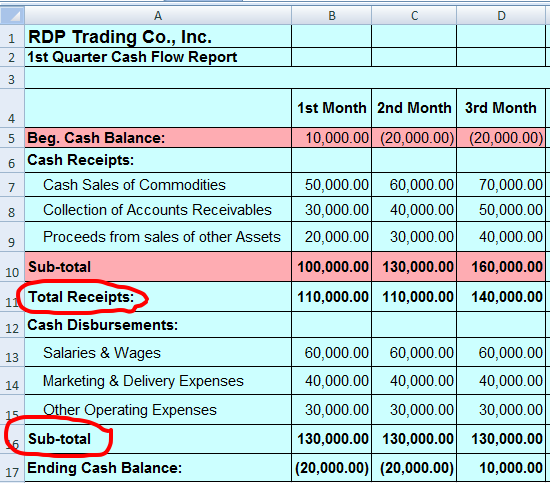

But other items do not carry any such commitment those in charge of the enterprise are free to use the uncommitted part of the C/F for any purpose they wish (shareholders or ministers not objecting!). The two lists include some items that imply contractual commitments to pay out part of the C/F to persons outside the enterprise (i.e., interest, rents, income taxes, and sometimes dividends). The derivation of C/F is represented schematically in Figure 1, where the solid lines represent physical flows and the dotted lines represent the flows of cash which correspond to them but move in the opposite direction. The central idea in identifying the C/F is easy: it consists of inflows of funds that “belong to capital” i.e., that represents the remuneration of capital in whatever forms it may take. The “cash flow” (C/F) refers to one specific stream of cash, one that can be derived from those named but one we have not yet separated out. Which of these flows of cash is the “cash flow”? None of them.

These flows include capital funds for construction the cash receipts (total cash income) after operations start outflows of funds to suppliers for raw materials, fuel, electricity, and for transport, banking, and advertising services regular weekly or monthly payments to labor interest and debt amortization payments to bankers or bondholders dividend payments to shareholders and tax payments to government.

#Cashflows at begining of project how to

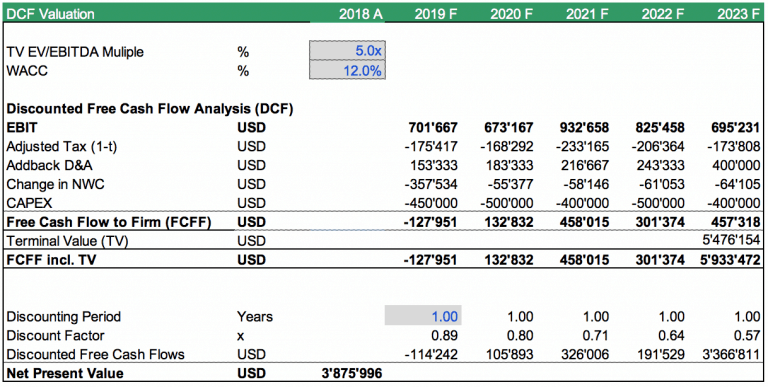

But others cannot hope to understand these claims for the method until they have gone back to “square one.” First one has to understand what a Cash Flow is, why and how to discount it, and then what one can do with a DCF once he has it.Įvery project has cash flowing into and out of its accounts, both during construction and after operations begin. The Discounted Cash Flow method can often give us a much better measure of a project’s profitability, for three main reasons:ĭCF washes out year-to-year variations in profit and gives us a single valid figure for the whole life of the project.ĭCF automatically takes into account the timing of cash payments and receipts, so that no one can neglect the importance of this factor.ĭCF gets around the difficulty of interpreting what accountants mean by “profit” and gives us a simple, unambiguous definition based on project earnings over the entire life of a project.Īll these points are well known to those already initiated into the mysteries of DCF. Furthermore, the ordinary one-year measure of profitability takes no account of the length of time that may separate the capital expenditures and the returns they eventually produce. It is a one-year figure, for some actual or representative year, after deducting allowances for taxes and for depreciation both these items can be highly arbitrary. The ordinary language of business treats the rate of profit as the ratio of (a) accounting profit in a representative year to (b) the amount of capital tied up in the enterprise, as measured by Net Fixed Assets or Net Fixed Assets plus inventories.

But a lot of businessmen and economists have discovered only within the past decade or so how useful and important this concept is. The world of money and finance has understood DCF (without calling it that) for as long as compound interest has been with us, which is quite long. The author explains what is involved.ĭISCOUNTED CASH FLOW stands for a modern and fast-spreading technique for the evaluation of investment proposals.

The phrase “discounted cash flow” is increasingly met with in discussions of development projects as well as in regular commercial enterprises.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)